In the aftermath of the shooting of two police officers in Ferguson, Missouri, during a protest over the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown and all that ensued afterward — and came before — it became strikingly obvious how the protest movement today differs from the Civil Rights Movement which inspired it.

If you don’t believe me, consider what Charles Steele, Jr., president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference said during an NPR interview during the recent Selma to Montgomery March, and shortly after the police shooting. Two of his comments caught my attention.

First, he told NPR’s Melissa Block his reaction after hearing about the police officers being shot:

“The first thing when I heard it early this morning — I turned on the TV, and I mentioned to my wife in the motel here in Montgomery — I said, ‘Baby, that’s a good example of the lack of infrastructure of education — that you can’t leave behind a generation of people without educating them in the civil rights movement.’ They don’t have a civil rights infrastructure in St. Louis or Ferguson or throughout Missouri. And we are saying now let’s take a crisis and turn it into an opportunity of conflict reconciliation and of teaching the nonviolence about Dr. Martin Luther King and the philosophy of the civil rights movement.”

Block’s immediate follow up question was whether there were young people marching “who wouldn’t remember anything about 1965?”

Steele replied, “Most definitely. There are more young people in this march than the elder folks like myself.”

If I interpret Steele’s comments correctly, he seems to see a connection between young people who lack knowledge of some signature aspects of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1960s — particularly regarding nonviolence — and the shooting of the two officers. Although there have been some people arguing that the shooter wasn’t really a part of the protest, perhaps Steele has a point. That is particularly so, if you consider that whether or not the shooter in this instance was a protester, the demonstrations in Ferguson have several times been marked by violence, rioting, looting and vandalism.

Some will argue that the violence began with the police, and that some outbursts arise naturally from the outrage of seeing a young black man killed in a community which the U.S. Department of Justice has called out for systemic abuses, mistreatment, and discrimination against the African American community by Ferguson’s municipal administration.

But the exact same things were happening in Birmingham in the 1960s, where Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor not only allowed Klansmen into the ranks of police — with consequent and frequent harassment of black citizens — but later used both the police and fire departments in violent efforts to suppress demonstrators. Moreover, in Birmingham, ordinary citizens who favored segregation, as well as members of the Klan or related white supremacist groups, often felt empowered to heap abuse on protesters.

Yet, somehow, demonstrators here in 1963 managed –for the most part — to maintain their adherence to nonviolent protest.

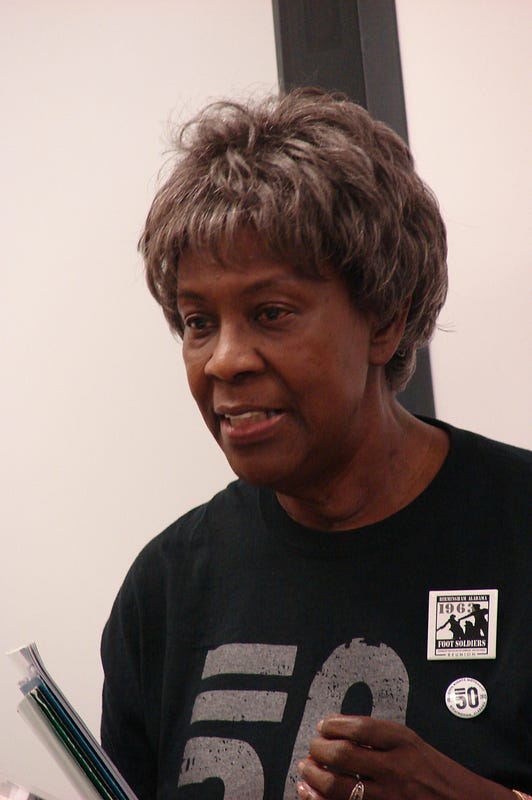

When I was interviewing people for Birmingham Foot Soldiers: Voices From the Civil Rights Movement, about the 1963 movement here, two things were absolutely clear: there were a lot of young people in the movement back then, but they were relentlessly trained by the leaders of the movement to be nonviolent.

Myrna Carter Jackson relates what was said to her group during a pre-demonstration meeting with King aide Andrew Young:

“We were gathered in the basement and they told us the rules and the regulations. ‘If anybody says anything to you all, spits on you or anything — you couldn’t say a word.’ We had to make that commitment. They said, ‘if you cannot do that, then you cannot demonstrate. There’s other things you can do, but you can’t demonstrate if you can’t take it. Those of you who feel like you can take it, that’s who I need.”

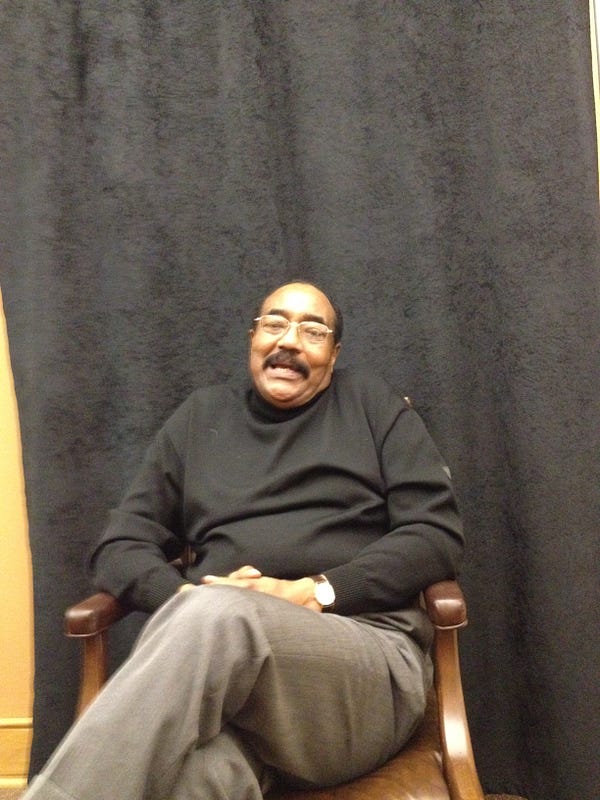

Clifton Casey recalled that “he found himself at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, listening to an orientation from James Bevel before the march. Bevel told them not to carry knives and to be determined not to fight back when confronted.”

Gerald Wren, who proclaimed himself a militant resister of Birmingham’s segregation by law, told me that getting involved in the formal civil rights movement meant fighting any urge towards violent response.

“You had to be able to absorb that spit, or that kick,” Wren said. “You see what I’m saying? The oldest is going to be in the front, and the oldest is going to be in the back; the youngest people gonna be in the middle. But you can’t hit that fella if he spits on you because you got people behind you that are gonna get hurt.

“That’s why they tell you, ‘You got any knives? Leave ’em. Put it in the basket. You can’t be carrying no arms because it’s nonviolent. You don’t want that. Because it’s a nonviolent thing. You can’t stand to get spit on, don’t get in the line. If you can’t get slapped, don’t get in this line.’ So that eliminated a lot of people.”

Terry Collins said that when he went to meetings to get organized for protests, among hundreds of young people from all over Birmingham, “The first thing we heard was the indoctrination about nonviolence, telling us that if we could not be nonviolent, then you couldn’t be in this with us.”

Could knowing about — or being relentlessly drilled in — the scrupulous devotion to nonviolence that gave Birmingham protesters the moral high ground in the eyes of the national and international community make a difference to demonstrators in Ferguson and other communities facing similar issues?

Honestly, I don’t know. But I do know that many young people today lack a great deal of knowledge about the civil rights milestones of preceding generations. That’s even true in Birmingham, where I sometimes try to teach journalism to college students. Several interesting encounters with students in a recent news writing class brought this point home.

Students were working in teams to write stories — they picked their own angles of approach — about race relations. One student, about 20, doing research, ran across an unfamiliar word, and brought her laptop to me to ask what it was.

“Apartheid,” I said.

“What does it mean?” she said.

Working through my shock, I explained a little about the history of racial segregation and oppression in South Africa, which I was just learning is no longer common knowledge among smart young people in 2015.

Later, right after class, I was talking with another student, this time a 20-year-old young woman from Nigeria. Thinking that, unlike her Alabama-born classmate, this young woman would know more about a significant piece of human rights history that happened on her home continent, I asked what she knew about apartheid.

“What?” she said.

“Apartheid,” I said again, trying to enunciate more clearly.

“Spell it,” she asked. I did. She still didn’t know.

I asked her if she knew who Nelson Mandela was. She said, “A freedom fighter.”

“What did he fight against?” I asked.

“Slavery?” she asked.

Again, I tried to explain. But wait, there’s more.

Between the first encounter, and the last, there were two others. First, two students approached, who — despite the intelligence they had both demonstrated in previous classes and assignments — were unsure what the term “race relations” means.

Second, three students who told me they had heard of the movie “Selma” — and planned to interview other college students about what happened in that town — also told me they had no idea that Birmingham used to be segregated, too.

During my five minute sketch of history, one of them — who had an expression of surprise on her face the whole time — said, “I thought that kind of thing only happened in south Alabama.”

So there you have it: a microcosmic study in how easy it is to forget. Or never to know.

On more than one occasion, I’ve heard people say — sometimes passionately — that it would be best to forget about the past and the painful experiences that emerged from segregation, Jim Crow, apartheid and the like. The evidence suggests that some have indeed forgotten. And some may feel that it’s a sign of progress — that the current generation of young people may not be burdened by the hateful baggage of the past.

But the question raised by Ferguson’s aftermath and other incidents as well, is — is forgetting what came before really the path to peaceful coexistence?